How To Develop A Project Plan For A Short-Term Project (487)

Many of the tasks that your Open Africa route will tackle will be projects – in other words, they will be activities with an aim, a beginning and an end. Short-term projects can last a few days or up to a few weeks, and will usually have only one or two objectives. For instance, it could be a brochure showcasing the route, its members and the surrounding area. Once the Route Forum has discussed the idea and a plan has been approved, it may only take a week or two to put the brochure together.

In this example, the objective is clear: a neatly printed, colourful and informative brochure that will encourage tourists to visit. There may also be another aim: to distribute the brochure to strategic places where potential visitors will pick it up.

To ensure that the project is carried out efficiently (without wasting time, money or resources) and on time, a plan is necessary. This will plot which activity will be done when, and by whom.

This Guide will explain how to prepare a plan for a relatively small project that needs to be completed in a short time. A plan is an important tool to help your route to run more professionally, efficiently and procedurally:

- It makes you more professional by ensuring that the right people are involved at the right times, to deliver a high-quality result in an orderly way.

- It makes you more efficient because you can research and decide (in advance) how everything should be done, and you can compare options until you find the best one.

- Being procedural means acting in accordance with the route’s policies and broad objectives – so that the organisation advances in the right direction and with the blessing and involvement of all members.

The main message of this Guide is that a good plan is the beginning of a good project; if the route fails to plan ahead when it implements its ideas, the result is usually a chaotic and costly activity that undermines the confidence of both the route’s members and its stakeholders.

Alongside this one, also read the Guides on How to Develop A Project Idea, How To Develop A Project Budget, and How To Manage a Short-Term Project.

Why is a project plan important?

A route works differently to a small business. As an owner of a small business, you can make most decisions by yourself and implement them in your own way. The route, on the other hand, needs management and for members to work together in a co-operative style, because the route is made up of members and is there to act in the interest of the members.

This means that more discussion is usually needed so that agreement can be reached on what activities should take place. Part of this discussion is about the planning, because members need to agree on how things are going to get done before they get done. So, a project plan is part of making sure that everyone is happy with an idea and the way it will be implemented.

It is also a good way for the route to mandate a person (or committee) to carry out important tasks in the interest of the route as a collective body. It improves the chances of success and ensures that the route works collectively towards its goals and objectives by co-ordinating everyone’s input and predicting where problems might occur.

What is a project plan, and how do you develop one for a short-term project?

A project plan is a map of how an activity will be implemented, bringing together the skills, money and other resources over a period of time to make it happen in an orderly fashion. Here we want to focus on how to plan for a short-term project – an activity that will take a matter of days up to a few weeks at the most.

Governance

A short-term project will usually consume less money than a medium-term or long-term project, and so will usually need fewer decisions to be made by the Route Forum; the more money is at stake, the more carefully the Forum must check and monitor expenditure and implementation. (For some guidance on turning an idea into an activity, read the Guide entitled How To Develop A Project Idea.)

But even a small project needs to follow a process of being considered and approved by the Route Forum or its designated subcommittee. Before it can make a final decision to allow a project and/or to commit route funds to it, it needs to see a step-by-step plan of how the project will roll out and where the money will be spent.

Timeline

Keeping the project on time will be important, especially if it only runs for a short period. What the project plan needs is a schedule – a timetable that says when each aspect of the activity will take place. So start by breaking up the project into smaller parts and placing them in order on a timeline. Give each task or activity a certain timespan during which it can be completed.

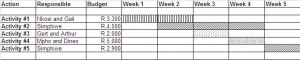

Below is a simple Gantt Chart that shows which activity takes place during which week; this example also shows who is responsible for that activity, and the available budget amount.

Budget

Breaking up the tasks also helps the project manager to research the various costs that the project will incur. These costs must be closely estimated by getting quotes from suppliers and service providers in writing so that you can hold them to these costs when the project goes ahead.

Working out the budget in advance is one of the main reasons for doing the plan; it allows the route to see what the project is going to cost before it takes a decision on whether it can go ahead.

People

When setting out the activities in a timeline, you should be able to estimate how many people are needed to get the job done in the time available. Assign a responsible person for each activity. If time is short, then you may need to get more people involved to complete it. This will then also affect the budget.

The plan is now able to help you to:

- Schedule tasks.

- Allocate tasks to responsible people.

- Monitor the project’s progress.

Responsibility and communication

The plan also needs to be clear on lines of responsibility, in other words, who is responsible for making what happen. Each task is usually given to the person or people with the relevant skills, and they are expected to complete the work in the required time and to manage those other people who are helping.

The person who takes overall responsibility is the project manager, who needs to ensure that all aspects of the project are being implemented according to plan. In a small organisation, that project manager will usually also be ‘hands-on’, doing a lot of the actual work themselves.

The project manager must also plan the lines of communication between everyone involved. For instance, everyone involved must know who to give certain information to, such as when a task is completed or when there is a problem, or when more help is required. In a small, short-term project, there may not be the time or need for written progress reports. But the manager needs to be doing much listening and much communicating.

Depending on the type of project, consider meeting (even only briefly) each morning with all involved to assess the previous day’s progress, to find solutions to any problems encountered, and to confirm what is to be done that day. If the team can only meet less often, consider meeting on a Monday morning to plan the week, and on Friday afternoon to assess progress.

Who is involved in project planning?

The Route Forum will need to oversee the planning and authorisation of projects, and may also have to appoint a project manager to take control of the planning and implementation process. The Forum’s Treasurer will usually have to help develop the budget and must then also help control the spending.

The route will also want to make use of the skills and capacity of its members, so there may also be a number of members involved. If possible, the route’s strategic partners will play a role in certain projects; they may contribute funding or they may help with implementation.

How do you apply project planning to the route?

Most of the route’s activities must be planned, and to plan them as a project is good organisational discipline. It gets everyone (the Route Forum, the members and the other stakeholders) into the habit of thinking through ideas and opportunities before rushing into them. And it encourages everyone to implement these ideas carefully and efficiently through a planned process.

Try and plan ahead so that all your route’s projects for the year are incorporated into the annual route plan (read more in the Guide on How To Compile Your Annual Route Plan).

Practical tips

- Once the project idea has been accepted and the project has been given the go-ahead, have one meeting dedicated to brainstorm the best ways of implementing the project. Build the best strategies into your plan.

- Keep the project plan as simple as possible so that everyone understands and follows it.

- When thinking through all the steps (or tasks) in the project, think about what could go wrong. Ask the “what if..?” questions, such as “What if the building materials are delivered late?” Try to build a solution into the plan. Allow some extra time if you can for these sorts of contingencies.

- Put as much of the plan as possible into a visual format – diagrams and tables (such as the Gantt Chart) – and put these up where everyone can see them. Refer to them in your regular meetings.

- Adjust and adapt your plan as conditions change – don’t abandon it. Even when you run into problems, you still need deadlines to aim for.

Use of this Guide

This Guide can be used by the Route Forum to help clarify its role when wanting to get projects off the ground. It can also be used by route management, who will often be the ones to plan and implement projects. Members will also find the guide useful, because they need to be involved and they should understand the process.

Other Factsheets and Case Studies

Here are some other factsheets in the Open African Toolkit that can help you with developing and managing projects:

- Guide: How To Develop A Project Idea

- Guide: How To Develop A Project Budget

- Guide: How To Manage A Short-Term Project